Domestic Violence Advocate Training for Covert Abuse and Coercive Control

For domestic violence advocates, understanding nuanced and often-hidden forms of abuse is crucial for providing comprehensive support to survivors. Recognizing this need, WomenSV has developed a domestic violence advocate training resource to familiarize advocates with covert abuse and coercive control.

Coercive control, covert abuse, emotional abuse, financial abuse, technology abuse and stalking represent a spectrum of manipulative tactics used by abusers to exert power and control over their victims. These forms of abuse can be challenging to identify, as they are frequently masked by behaviors that appear normal or are hidden behind closed doors. In this training, advocates will gain tools to support survivors navigating their complex and often misunderstood experiences. The goal of this resource is to provide domestic violence advocates with the knowledge and resources necessary to effectively recognize and address subtle forms of abuse.

Allies and survivors may also find this resource helpful, so please feel free to share this page with anyone you think may benefit from the information.

Please note that the information on this page is intended to supplement, not replace, training for domestic violence advocates. The information on this page is provided for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal or medical advice.

What is the legal definition of domestic violence?

What is the legal definition of domestic violence?

Understanding the definition of domestic violence can help advocates and survivors determine what specific legal rights might apply in a given location. If you are located in another state or country, make sure to check and compare your local government’s definition of domestic violence.

This is the legal definition of domestic violence under federal law:

Domestic violence is a pattern of abusive behavior in any relationship that is used by one partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner.

Domestic violence can be physical, sexual, emotional, economic, psychological, or technological actions or threats of actions or other patterns of coercive behavior that influence another person within an intimate partner relationship.

This includes any behaviors that intimidate, manipulate, humiliate, isolate, frighten, terrorize, coerce, threaten, blame, hurt, injure, or wound someone.

This is the legal definition of domestic violence under California law:

Domestic Violence is abuse committed against an adult or any minor who is a spouse, former spouse, cohabitant, former cohabitant, a person with whom the suspect has had a child or is having or has had a dating or engagement relationship. Same gender relationships are included.

Abuse means intentionally or recklessly causing or attempting to cause bodily injury, or placing another person in reasonable apprehension of imminent serious bodily injury to himself or another.

Coercive Control in California Law: Family Code 6320

Coercive Control in California Law: Family Code 6320

Until fairly recently, the legal definition of domestic violence in California excluded subtle forms of abuse that do not always leave forensic evidence behind. However, California Secretary of State has amended Family Code section 6320 to add an expanded definition of “disturbing the peace of the other party” within the definition of “abuse”.

This information is important for survivors of coercive control in California because the revised FC6320 includes coercively controlling behavior as grounds for a restraining order, which if violated can become a criminal case. California is one of the few states in the country to have a law that recognizes coercive control.

According to Family Code 6320:

(a) The court may issue an ex parte order enjoining a party from molesting, attacking, striking, stalking, threatening, sexually assaulting, battering, credibly impersonating as described in Section 528.5 of the Penal Code, falsely personating as described in Section 529 of the Penal Code, harassing, telephoning, including, but not limited to, making annoying telephone calls as described in Section 653m of the Penal Code, destroying personal property, contacting, either directly or indirectly, by mail or otherwise, coming within a specified distance of, or disturbing the peace of the other party, and, in the discretion of the court, on a showing of good cause, of other named family or household members.

(c) As used in this subdivision (a), “disturbing the peace of the other party” refers to conduct that, based on the totality of the circumstances, destroys the mental or emotional calm of the other party. This conduct may be committed directly or indirectly, including through the use of a third party, and by any method or through any means including, but not limited to, telephone, online accounts, text messages, internet-connected devices, or other electronic technologies. This conduct includes, but is not limited to, coercive control, which is a pattern of behavior that in purpose or effect unreasonably interferes with a person’s free will and personal liberty.

Examples of coercive control include, but are not limited to, unreasonably engaging in any of the following:

(1) Isolating the other party from friends, relatives, or other sources of support.

(2) Depriving the other party of basic necessities.

(3) Controlling, regulating, or monitoring the other party’s movements, communications, daily behavior, finances, economic resources, or access to services.

(4) Compelling the other party by force, threat of force, or intimidation, including threats based on actual or suspected immigration status, to engage in conduct from which the other party has a right to abstain or to abstain from conduct in which the other party has a right to engage.

(5) Engaging in reproductive coercion, which consists of control over the reproductive autonomy of another through force, threat of force, or intimidation, and may include, but is not limited to, unreasonably pressuring the other party to become pregnant, deliberately interfering with contraception use or access to reproductive health information, or using coercive tactics to control, or attempt to control, pregnancy outcomes.

What is coercive control?

What is coercive control?

Coercive control is abuse that involves a pattern of threatening, isolating and controlling behavior. This insidious, manipulative abuse escalates incrementally over time, making it difficult for victims to recognize the signs or seek help. It may start with behaviors as seemingly innocuous as jealousy or overprotectiveness but can quickly evolve into a comprehensive strategy to isolate and dominate the victim entirely. The perpetrator ultimately dominates the victim's daily life, eroding their sense of autonomy and self-worth. Coercive control can include emotional abuse, financial abuse, legal abuse, technology-facilitated abuse, sexual abuse and physical abuse.

Coercive control can manifest as overt (obvious) or covert (subtle) abuse. It encompasses a wide spectrum of actions, from manipulation to severe physical aggression. It could be an overt show of violence - punching the wall with the implication that “you’re next if you don’t get into line” - or indirect, implied threats. You don’t have to put your hands on someone to intimidate them, control them or make them feel trapped.

Examples of coercive control include:

Emotional manipulation: Gaslighting, guilt-tripping, shaming and instilling fear.

Physical abuse: Ranging from the destruction of property to strangulation. Approximately 40% of survivors that seek assistance from WomenSV report non-fatal strangulation at the hands of their partner.

Technology-facilitated abuse: Using technology to monitor, harass or control a partner’s activities.

Financial abuse: Controlling all household income and expenditures.

Legal abuse: Manipulating legal systems to harass or control the victim.

Isolation: Severing the victim’s connections with family and friends, making it difficult to seek help or escape.

Gender dynamics in coercive control

While coercive control can affect anyone, regardless of gender, it is predominantly a gender-based crime, with the vast majority of victims being female and perpetrators male. However, it is important to acknowledge that men can also be victims, women can be perpetrators, and children can suffer from coercive control by either parent.

Social stigma and shame

Victims of coercive control often remain silent due to the profound sense of shame and the social stigma attached to domestic violence, especially in affluent areas. The perpetrator may leverage this shame to further isolate and control the victim, making it even harder for them to acknowledge their situation and seek help.

Coercive control is a lethality risk.

Perpetrators of this kind of abuse treat intimate partners, children or family members like resources, objects and possessions to be used, used up and then disposed of when no longer found to be useful. Coercive control is a lethality risk because the ultimate right of property possession is disposal.

Dr. Evan Stark, researcher and author of Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life, describes coercive control as a liberty crime that violates the fundamental right to freedom and safety at home. It erodes the victim’s sense of agency, self-sufficiency, independence and over time, their sense of self, of personhood. In a way, it's the ultimate form of identity theft as it robs the victim of who they once were before all these things - their freedom, their peace, their safety, their independence - were taken away.

Overt coercive control

Overt coercive control

Some forms of domestic violence and coercive control are are easy to recognize, like physical violence - especially if it leaves blood, broken bones or bruises behind. Overt abuse is obvious aggression that can be quickly recognized: if the abuser is waving a gun in his partner’s face, driving 90 mph to scare her or kicking her out of the house and forcing her to spend the night sleeping in her car because she has done something to make him angry. But words can be weapons too.

Verbal examples of overt coercive control:

Threatening:

“I love you so much, if you ever leave me, I will hunt you down and kill you.”

”If you leave me I will tell all your friends how crazy you are.”Controlling:

”Put this app on your phone / add me to Find My Friends so I know where you are.”

”Tell me all your passwords.”

”No, you are not going to spend a weekend with your friends.”

”You can’t have any friends of the opposite sex on social media.”

”When I call you, you’d better pick up by the second ring.”

Physical examples of overt coercive control:

Fist to the face

Knife to the throat

Sleep deprivation

Blocking an exit

Harming a partner’s child or pet

Driving dangerously to scare or intimidate

Covert coercive control / covert abuse

Covert coercive control / covert abuse

Covert coercive control or covert abuse involves the use of subtle tactics to control, intimidate, isolate or threaten an intimate partner. This kind of abuse typically leaves no forensic evidence behind. It’s hard to prove, hard to identify, hard to defend against and over time it can make the victim of this kind of crime begin to think she is losing her mind. This is especially true when it involves gaslighting.

Gaslighting refers to the psychological manipulation of a person usually over an extended period of time that causes the victim to question the validity of their own thoughts, perception of reality, or memories. Gaslighting is a form of emotional abuse that typically leads to confusion, loss of confidence and self-esteem, uncertainty of one's emotional or mental stability, and a dependency on the perpetrator.

Source: Women’s Aid Dundalk

Verbal examples of covert coercive control:

Veiled threats:

“You don’t want to see me mad.”

”You have no idea what I’m capable of.”Gaslighting:

“That never happened.”

“You might want to consider talking to someone—you’ve been under a lot of stress lately.”

In response to something she saw him do: “I would never do that.”

In response to something she heard him say: “I would never say that.”Sharing “concern” with their friends, kids’ teachers about her mental state as a way of planting seeds to discredit her.

Physical examples of covert coercive control:

The silent treatment

Taking out a gun and cleaning it to intimidate a partner during an argument

Personal belongings start to go missing. Medication goes missing after an argument. Car keys go missing the morning of an important job interview.

Imposing punishment on a partner for breaking one of their rules. “Accidentally” locking her out of the house because she came home after “curfew”.

Financial abuse

Financial abuse

Financial abuse is common form of abuse in affluent areas. It’s one of the main reasons why a woman stays in an abusive relationship and one of the main reasons why she goes back after leaving. Sometimes a choice is made to return to an abusive relationship because the alternative is being homeless - over 50% of women who experience homelessness end up there as a result of domestic violence.

Financial abuse often results in the abuser controlling all the resources in a relationship, even if his partner participates in earning them. The victim may drive a fancy car but have no access to a joint bank account and no spending money of her own, even if she has a high-paying job.

Examples of financial abuse include:

Controlling access to funds

Restricting access to joint accounts

Putting her on an allowance or “stipend”

Punishing “over-spending”

Forcing partner to turn over money she has earned

Hiding assets

“Embezzlement”, forging documents

Income tax evasion without the other partner’s knowledge

Threatening to render her penniless or homeless if she leaves

Forcing her to take out loans

Forcing her to make early withdrawals from retirement accounts

Forcing her to sign restrictive prenuptial

Stealing social security checks

Frivolous, costly litigation / legal abuse

Coerced debt; debt as a means of exercising abusive control

Technology-facilitated abuse

Technology-facilitated abuse

Technology-facilitated abuse refers to the use of technology to stalk, harass, intimidate and control. This alarming phenomenon is increasingly prevalent among tech-savvy abusers, yet victims are often disbelieved and written off as being paranoid.

Examples of technology-facilitated abuse include:

Hidden cameras in the home

Smart cars and smart home devices used for tracking and surveillance

AI-generated intimate images used to blackmail or damage the victim’s reputation

Requesting intimate images during the relationship only to later use them for blackmail and harassment after the relationship ends

Online harassment, such as on social media platforms or through the use of websites to mount a smear campaign

Stalking

Stalking

Stalking involves a pattern of harassing or threatening tactics that are unwanted and cause fear in the victim. It can be physical or technological, such as following or spying on the victim.

Stalking is another form of coercive control - and another lethality risk. According to forensic psychologist Reid Meloy, 80% of domestic violence victims killed by their partner had been stalked. He warns that the closer the relationship is or was, the more seriously the threat should be taken.

The Power and Control Wheel

The Power and Control Wheel

Source: DomesticShelters.org

(click image to enlarge)

The Power and Control Wheel was developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minnesota to describe tactics that abusers use on their victims. It illustrates several elements of coercive control that can be observed in abusive relationships:

Using intimidation

Using emotional abuse

Using isolation

Minimizing, denying and blaming

Using children

Using male privilege

Using economic abuse

Using coercion and threats

The escalation process: the slippery slope of abusive relationships

The escalation process: the slippery slope of abusive relationships

Abusive relationships rarely start with abuse. Abusers are often incredibly charming, devoted, attentive in the early stages of a relationship. Because they look so good in the beginning and because we tend to give people the benefit of the doubt, some of their behaviors can be mistaken for expressions of love. Through a gradual escalation process, abusive relationships go down the “slippery slope” over time.

“Love bombing” refers to an intense and overwhelming display of affection, admiration, and attention given by one person to another, typically in the early stages of a romantic relationship or during the grooming phase of manipulation in an abusive relationship. The term originates from the idea of "bombarding" someone with expressions of love and affection, often to the point of making them feel overwhelmed or unable to resist the affectionate advances. Love bombing can be a tactic used by manipulative individuals or abusers to gain control, establish a strong emotional bond, and manipulate the target into becoming dependent on the affection and attention provided. It can ultimately serve as a precursor to more controlling and abusive behaviors.

For example, he may shower his partner with attention and gifts, telling her she’s so much smarter than any other woman he’s dated, or so reasonable compared to his crazy ex-partner.

Over time, red flags will begin to appear: a little road rage here, a little teasing there, a little suggestion here or there about what she should eat or how she should wear her hair. It could be perfectly innocent, but only time will tell whether these suggestions are meant to help her or control her.

Early on, he might send her text messages all day, every day. He’s thinking about her, missing her, wondering what she’s up to, wishing she were here with him — and in the beginning, doesn’t it look a lot like love? But is it really love, or is it something more insidious? Love bombing involves showering her with attention and affection to sweep her off her feet!

If he wants to spend every waking moment with her, that kind of attention can be intoxicating. As time goes on, it can look more and more like stalking.

He may slowly start to be controlling in more and more areas of her life — who she sees and what she does when she’s not with him, what she studies at school, whether to take that promotion.

As an example: a writer shows her partner a project she’s working on. In the beginning he may be full of praise, but over time, he may suggest an edit here, deleting a sentence or paragraph there or finding a different topic altogether to write about, to the point where she may end up having difficulty putting pen to paper at all.

Over time, she may start to feel isolated, like she can’t spend as much time with friends or extended family members anymore. If she does try to see them, he may make her feel guilty about it, or give her the silent treatment afterwards.

He may start chipping away at her self-confidence, with comments like:

“I don’t know if that’s your color, honey....”

“Are you sure you’re ready for that promotion?”

“You really want to abandon your family and go back to work? You don’t have to work. I’ll take care of you.” (And when she gives up her career to raise their children, he ends up calling her a useless, lazy parasite.)

Or the abuse may begin under the guise of...

“Here, let me help you…”

“Here, let me help you install that software on your computer.” Later, she realizes he used the software to monitor her activities.

He’s a financial analyst so it only makes sense for him to take care of the books — and she likes to cook so it seems like a fair division of labor — until she finds out later he’s been “cooking the books” aka siphoning off money from the joint account!

Over time, it can progress to:

“What took you so long to get home? Why didn’t you pick up the phone? I’ve been calling you all night.”

“Why are you spending so much time with your friends—do you prefer them over me?”

“Who was that guy you were talking to at the party?”

Over time he may begin to make more comments or suggestions about how much makeup she should wear, how to dress, what to wear, what to order in a restaurant, what to cook at home, how to cook it, how to clean up, where to shop, where not to shop, what to eat, who she can spend time with when she’s not with him, what to do with her own money…

These suggestions can turn into pressure and there can be a price to pay if she steps out of line: the silent treatment (sometimes for days), or her car keys go missing when she is heading out the door for work, or a date she was looking forward to suddenly gets cancelled.

It’s about power, it’s about boundaries: testing, probing, breaching, seeing what he can get away with. That’s how the subtle erosion of her freedom happens, a little bit at a time. It’s incremental— slowly it chips away at your your peace, your happiness, your independence. It’s death by 1,000 cuts.

It’s also about how she feels when listening to her gut instincts. To clarify this, she might want to ask herself:

How do you feel after spending time with him? Lifted up? Or put down? Worried about making him mad? Starting to be afraid of his anger?

Is he getting moody? Giving you the silent treatment more and more often? Is it lasting longer?

Are you starting to avoid certain topics to avoid setting him off?

Are you choosing your words more carefully?

Are you feeling less and less free to speak your mind and be yourself?

Coercive control is a slippery slope, but once it begins, there’s nowhere to go but down. It starts off so innocently with charm and love bombing. She gets swept off her feet and before she knows it, he is beginning to control her, manipulate her and gaslight her into submission.

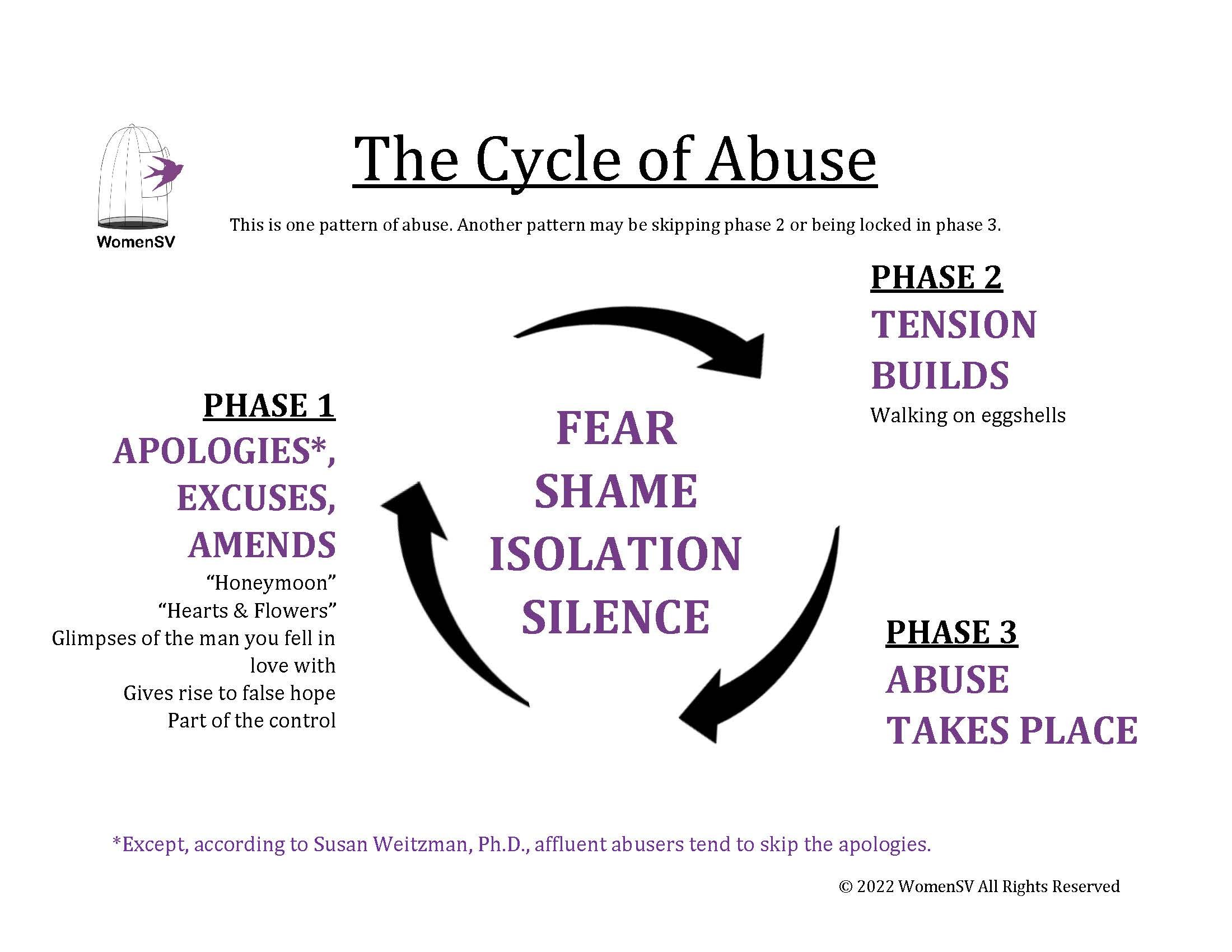

The Cycle of Abuse

The Cycle of Abuse

The cycle of abuse or cycle of violence is a pattern that emerges in abusive relationships. While abusive relationships do not always follow this pattern, they often do.

The cycle of abuse has three phases:

Honeymoon / loving reconciliation / hearts and flowers

Tension builds

Abuse incident takes place

Often they meet during the “honeymoon” period, when he is on his best behavior. Then over time, the mask begins to slip, tension mounts and there is an explosion of emotional, verbal, physical or sexual abuse. The incident is followed by a cooling-off period where he goes back to being the person she was first attracted to.

The confusion and cognitive dissonance caused by this behavior makes it likely that she will forgive these outbursts, and give him another chance. The periods of peace throw her off balance because they resurrect that false hope that he will go back to being the partner she fell in love with and this time it will be different.

What she often comes to realize over time is that even those periods of peace are part of the control he exerts over her, because it's those quiet moments of peace that keep her in the relationship. The intermittent reinforcement creates the trauma bond and makes it so much harder to break that cycle than if he were just mean and miserable all the time. The moments of peace can make it hard for her to recognize that she is in an abusive relationship, especially if she doesn’t have bruises or broken bones to show for it.

Fear, shame, silence and isolation are at the heart of this cycle. She is kept in the cycle out of fear, afraid of what he will do or say to her (or their children) if she steps out of line. Financial abuse can amplify her loss of autonomy and serve as another way to keep her trapped in a vicious cycle.

Recognizing covert abuse survivors and perpetrators

Recognizing covert abuse survivors and perpetrators

Subtle forms of abuse can be difficult to recognize, as they often happen privately and leave little forensic evidence behind. Sophisticated abusers are skilled at maintaining a public image that differs from who they are behind closed doors.

“Considerable research reveals that most people, including mental health and law enforcement professionals, are remarkably poor at catching liars, doing no better than chance,” reports forensic psychologist Shawn Adair Johnson.

In order to recognize covert abuse perpetrators and their victims / survivors, it’s important to remember:

Covert abusers and survivors do not always fit a “typical” profile or stereotype!

Covert abuse and coercive control happen across occupations, genders, races, sexual orientations, age groups and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Doctors, therapists, religious leaders, celebrities and “successful” people can be perpetrators or victims of this type of abuse, even if they seem productive and well-established / respected / regarded in the outside world.

Covert abuse is not limited to certain geographic locations or neighborhoods, though it often goes unreported in higher-income areas. In affluent areas regardless of cultural background, there can be tremendous shame and stigma attached to being a domestic violence survivor, which often keeps survivors silent and feeling trapped.

No community is immune to the abuse of power and unfortunately the more power, money and influence an individual has, the more tools they have at their disposal to wield and abuse that power.

Understanding sophisticated abusers

Understanding sophisticated abusers

What does a covert abuser look like?

The honest answer is, they look like everybody else. You can’t tell by looking!

It’s the therapist who puts his wife on a psychiatric hold after she tells him she wants a divorce.

It's the businessman who hides his income and forges his wife’s signature on the income tax return.

It's the cybersecurity expert who puts spyware on all her electronics, and hidden cameras in the home and in her car.

It’s the journalist who uses words as weapons and mounts a smear campaign to damage an intimate partner’s career and reputation, sprinkling truth in with the lies to make the lies more credible.

It's the physician who terrorizes his wife by telling her how he’s going to kill her by injecting her with a poisonous solution between her toes - in a place that not even the coroner will think to look. Or perhaps he says casually over dinner one night, “Do you know there's more than 40 ways to kill a woman and make it look like she died from natural causes?”

The problem is that covert abusers are very difficult to spot - even for the seasoned professional! And that’s how they get away with it - because they walk amongst us like regular people and are very skilled at impression management. They also play on our own tendency to take people at their word, especially if they are Harvard educated, have an M.D. or Ph.D. after their name and are well-respected in the community.

As researchers, psychologists and world-renowned experts in psychopathy Paul Babiak and Robert D. Hare wrote in their book Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work: “Merely having a mental checklist of the traits that define psychopathy does not guarantee success in spotting the psychopath. In fact it is not uncommon for well-trained researchers in this field of study to be fooled and manipulated by known psychopaths they have just met.”

As forensic psychologist Reid Meloy puts it: “Even a seasoned professional can be fooled by a seasoned liar.”

So how do you recognize a covert abuser? Understanding the behaviors, patterns and underlying motivation associated with covert abuse is the key.

Common characteristics of covert abusers include:

Lacking empathy, remorse, self-reflection, conscience and moral maturity

Appearing to enjoy causing pain or fear to those they should protect the most

Lying easily, often and convincingly

Including fabricated but precise details in their communications to make them sound authentic, sprinkling truth in with lies, planting seeds of doubt to undermine their victim’s character

Blaming their partner or others for everything

Lacking self-reflection or accountability, never acknowledging their own abusive behavior or mistakes - they must always be right

Minimizing or denying their harmful behavior

Playing the victim even when they are clearly the perpetrator

Shaming others

Viewing relationships similarly to war, business or a game of chess

What motivates a covert abuser?

Covert abusers are motivated by power, social status, money, sex, winning, revenge, preserving their public image, and conquering / defeating / dominating / destroying anyone who gets in their way. While a healthy person strives to cultivate a sense of community and connection in their life, a covert abuser thrives on sowing seeds of dissent.

“In order to escape accountability for his crimes, the perpetrator does everything in his power to promote forgetting. If secrecy fails, the perpetrator attacks the credibility of his victim. If he cannot silence her absolutely, he tries to make sure no one listens,” explains Judith Herman, author of Trauma and Recovery.

Understanding victims and survivors of coercive control

Understanding victims and survivors of coercive control

What does an abuse survivor or victim look like?

Survivors of covert abuse and coercive control cannot be recognized by their appearance alone. This pervasive, insidious and tricky form of abuse often goes unrecognized even by those who experience it. Smart, well-educated, accomplished people are not immune to this type of abuse, though they might face additional pressure to keep up appearances as if everything is fine at home. A survivor is likely to be capable of empathy, remorse, self-reflection and compassion, all of which can be weaponized by the covert abuser. As a result, the survivor may not recognize much of the abusive behavior as abuse - and might even blame themselves!

Survivors of coercive control may display the following qualities:

Appearing frazzled, fragmented, fragile, scattered, “crazy”, paranoid, extremely anxious - likely due to trauma / TBI / PTSD, or their partner’s stalking, abuse, gaslighting and sleep deprivation.

Having a hard time remembering key details, remembering important facts or telling their story in a coherent, linear fashion. They might not present themselves well when discussing the abuse, which can impact their credibility to others.

Rationalizing the abuse or explaining it away, blaming stress, alcohol, work or the economy.

Coping with denial, numbing, dissociating, anti-depressants or self-medicating with drugs / alcohol / binge-eating / shopping / exercise.

Minimizing the abuse (so do abusers) and the amount of danger they are in.

Not fully confiding in anyone about the abuse.

Not recognizing their partner’s behavior as abuse.

Working well below their professional capacity due to trauma.

Appearing capable and take on responsibilities (professional or volunteer work) in the outside world while being powerless at home.

Appearing privileged to outsiders while having very little access to money of their own.

Appearing very confident, strong and unemotional - not fitting the typical profile of what you might think of as a battered woman.

Appearing “over the top” OR calm, confident, poised, “flat affect”—especially if in positions of power and authority themselves.

Blaming themselves — and so does their partner!

Desiring peace, settlement and / or negotiation.

They might come from healthy or unhealthy family backgrounds - they are equally vulnerable either way.

Being motivated by fear, shame, love, loyalty, culture, religion, family values

Often they will later deny the abuse, refuse to testify or “go sideways” from fear, regret, forgiveness, love, or their partner’s persuasion and coercion.

The more religious they are, the longer they tend to stay.

Why do survivors stay in abusive relationships even after recognizing that they are being abused?

There are many reasons why a survivor might be hesitant to leave an abusive relationship, including:

Feelings of shame

Financial dependence (over 50% of unsheltered women report domestic violence as the cause of their homelessness)

Fear of what the perpetrator has threatened to do (ex: harm or kill her / the kids / himself / all of them, get custody of the children, “destroy” her, turn their children against her or disappear with the children)

Hoping to “fix” the relationship, still loving him and thinking there is something she can do to “heal” him

Worrying she won’t be believed if she speaks up to report the abuse

Religious, cultural or familiar pressure

Isolation

Avoid asking the following unhelpful questions to survivors of domestic abuse:

Why didn’t you just leave?

Why did you stay so long?

Why didn’t you call the police?

If it was so bad, why didn’t you tell anyone?

Impacts of PTSD on domestic abuse survivors

Impacts of PTSD on domestic abuse survivors

Post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD is common among domestic abuse survivors. Understanding PTSD and its impact on survivors can help prepare advocates for calm, compassionate conversations.

PTSD symptoms include:

Easily being startled

Feeling tense, on guard, “jumpy” or on edge

Difficulty concentrating

Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep

Irritability potentially leading to angry or aggressive outbursts

Risky, reckless, or destructive behavior

Trouble remembering important details of traumatic events

Negative thoughts about themselves or the world around them

Blaming themselves or others excessively

Persistent negative emotions like fear, anger, guilt, or shame

Loss of interest in activities they used to enjoy

Feelings of isolation

Difficulty feeling positive emotions like happiness or satisfaction

Understanding PTSD can be helpful for advocates because:

There is a cross-over between symptoms of PTSD and symptoms of other personality disorders.

Personality disorders are considered to be long-standing, enduring, fairly intractable and often difficult to treat. Individuals diagnosed with personality disorders are all too often written off by others as being “nuts”. They have diminished credibility with law enforcement, the courts, and many mental health professionals and intervention programs.

•A diagnosis of a personality disorder can negatively impact survivors in a number of areas, including: access to support and services; custody and visitation issues; law enforcement response; mental health response.

•Victims of domestic violence can look like they have a personality disorder or mental illness when they are in fact suffering the effects of trauma caused by the abusive relationship.

When survivors with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or traumatic brain injury (TBI) reach out for help, they might:

Struggle to recall details of abuse or retell events in a coherent narrative.

Leave out key details

Laugh, cry, speak in a monotone voice, seem “over the top”, appear “manic”, or present a fragmented story when describing violence. This may be compounded by TBI, sleep deprivation or their partner’s tactics to make her appear unbalanced.

This can affect a survivor’s credibility in the legal or healthcare system and support an abuser’s claims that she is “crazy”, dishonest and incompetent, claims that may be given more weight due to his power and influence in the community.

Especially if the survivor is a victim of technological abuse, and she confides in a provider who is not tech-savvy, it can be easy to incorrectly conclude she is paranoid.

It’s important for advocates - as well as police, lawyers and judges - to recognize and understand the impaired cognitive functioning of domestic violence victims and consider that the reason their story varies, leaves out important facts, or doesn’t have a coherent narrative structure may not be because they are lying or crazy but because they are suffering the effects of trauma.

Impact of coercive control on children

Impact of coercive control on children

Researching coercive control’s impact on children

There is currently little published research on what coercive control looks like in parenting - it’s a new field of study. In 2020, a research paper was published titled “When Coercive Control Continues to Harm Children: Post-Separation Fathering, Stalking and Domestic Violence.”

The research focused on fathers who engaged in coercive control with their children post-separation, and reported:

“Fathers can use the same tactics of coercive control against their children that they use against their ex-partners.”

Children can be direct victims of coercive control and they can experience it in much the same ways as adults do – feeling confused and afraid, living constrained lives, and being entrapped and harmed by the perpetrator.

Coercive control can harm children and young people emotionally / psychologically, physically, socially and educationally.

Robust measures are required to deal with coercive control perpetrating fathers, in order to prevent them from using father–child relationships to continue imposing coercive control on children and ex-partners.

The ACE Study

The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study measured categories of childhood trauma and their potential impact on lifespan. Visit the following resources to learn more:

Trauma-informed tips for advocates working with survivors

Trauma-informed tips for advocates working with survivors

What can you do if you think someone is suffering from covert abuse?

Abuse thrives in secrecy, silence, shame and isolation. Advocates can help survivors break the silence by starting the conversation in a collaborative (not commanding!), compassionate manner.

Here are a few phrases that can be helpful:

I am concerned for your safety

I am concerned for your children’s safety

I am concerned that it will only get worse

You don’t deserve to be abused; no one deserves to be abused

It is not your fault

You are not alone, I am here to help you

That must have been hard for you. I’m so sorry you had to go through that.

There are resources that can help; you don’t have to do this alone!

General guidelines for serving survivors:

Practice empathy, patience and understanding

Allow the survivor to tell her story and interrupt only to clarify

Expect that the survivor’s story may leave details out or have inconsistencies, and she may have to retell the story to fill in gaps

Understand that survivors may experience memory loss due to trauma - to aid in recollection, does she remember other sounds or smells?

Don’t judge. Understand why she may have delayed coming forward out of fear, shame, not wanting to get her partner into trouble, financial reasons, love or hope of saving the relationship

Recognizing and responding when a survivor is in a trigger state

Learning how to recognize and respond to a survivor who is in a trigger state can help advocates offer trauma-sensitive care.

Recognize:

physical symptoms such as sweating or difficulty breathing

sudden and drastic changes in emotion, such as anger or fear

a desire to flee or hide – we can help them leave the triggering environment as quickly as possible

Respond:

we can let them know we’re there for them, that they are safe, that we will listen if they want to talk, while also assuring them that words are not necessary

we can be with them without touching them – and if we think physical contact might help, we can ask permission first

we must let trauma survivors know that we believe them, that their trigger responses are valid, and that none of this – neither the original trauma nor the trauma response – is their fault

What can you do to help protect the health and safety of survivors?

Recognize red flags

Listen, interrupt only to clarify

Meet them with validation and understanding. Validate their experience—don’t judge or pressure. Be sensitive to cultural differences that make IPV harder to identify/address—and that includes the culture of affluence

Affirm their right to live in peace and safety in their own homes

Reassure them that they do not have to deal with this issue alone anymore

Warn survivors against couple’s counseling because it can be dangerous to do with a covert abuser - the therapist can be manipulated by the abuser! Advise survivors to find a therapist well-versed in covert abuse and coercive control for their own individual therapy.

Connect them with resources

Understanding the danger of leaving an abuser

70% of reported domestic violence incidents take place after separation. The most dangerous times for a domestic violence victim are:

pregnancy

when the perpetrator suspects their partner is planning to leave

during the act of leaving the relationship

after the relationship ends

Reminders for advocates:

Abuse can escalate even after the relationship ends

If a survivor returns to an abusive relationship, abuse often worsens and it can become even harder to leave

Post-separation abuse and “flying monkeys: make survivors feel isolated and vulnerable. Survivors will need to gather allies and “build their village”: a trustworthy support system!

Survivors can confide in local police with an incident report if their department offers that service, or have an off-the-record conversation where they do not give their full name or address to a detective so they can learn about safety measures and what their options are.

Stalking is a lethality risk that is not always taken seriously by the police

Remind survivors to protect themselves professionally by confiding in co-workers that their abuser may try to contact them and ask them not to give out personal information or engage

Children affected by abuse may benefit from trauma-informed therapy

Self-care is not an option, it’s a vital necessity to care for mental health! Click here for self-care tips.

Screening tools for coercive control

Screening tools for coercive control

The Danger Assessment and the Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) Scale are two tools that can help when screening for coercive control.

The Danger Assessment helps to determine the level of danger an abused woman has of being killed by her intimate partner.

Source: dangerassessment.org

The Women’s Experiences with Battering (WEB) Scale is a series of 10 statements that can help survivors assess how safe or unsafe they are feeling. The respondent is asked to rate how much she agrees or disagrees with each of the statements on a scale of 1 to 6 ranging from disagree strongly (1) to agree strongly (6).

For survivors still in the relationship: Use the present tense version of the WEB Scale to gauge how safe or unsafe the survivor is feeling in the relationship. In responding to the statements, survivors can try to think of the worst incidents.

For survivors who have escaped the relationship: Use the past tense version of the WEB Scale to gauge how safe or unsafe the survivor is feeling. Escaping does not mean the fear goes away. Safety risk increases after leaving a relationship and spikes for at least two years, which is when most domestic violence incidents happen.

Coercive control attack and defense strategies

Coercive control attack and defense strategies

Coercive control involves attacking many different areas of a survivor’s life. To illustrate the various types of attacks and potential defense strategies for survivors, WomenSV has created a visual resource, the Attack-Defense Wheel.

The Attack-Defense Wheel below displays the different ways that coercive control survivors can be attacked on the left. On the right side are related strategies that survivors may want to use in defense.

A survivor of coercive control and covert abuse may experience attacks related to her career, education, housing, finances, social life, physical & sexual safety, spirituality, psychological / emotional well-being, spirituality, family and even her own identity.

Abusers may even go so far as to use the legal system against those it was designed to protect. A sophisticated abuser may use a tactic known as the “engineered restraining order” or “engineered 5150”, where they accuse their victim as a perpetrator of abuse. This can cause the victim to become arrested or put on a psychiatric hold (5150), damaging their credibility and taking away their freedom.

Countering these different forms of abuse requires a variety of strategies and resources specific to the type of attack.

(click image to enlarge)

Safety planning

Safety planning

Safety planning is vital for domestic violence survivors, whether they are currently involved in, planning to leave, or have already escaped from an abusive relationship.

Help survivors consider and answer the following questions to start the safety planning process:

Where can you go for help?

Who can you call?

Who can and will help you?

How will you escape if the situation becomes violent?

What can you do to increase your safety?

How can you protect yourself against a potential smear campaign afterwards?

For detailed information on safety planning, visit:

Resources

Resources

How to become a domestic violence survivor advocate:

Are you interested in becoming a domestic violence survivor advocate? You might want to consider specialized training to help survivors of coercive control, in addition to a 40-hour domestic violence advocate training.

Coercive control training:

Coercive control training classes teach advocates how to support survivors through the unique challenges presented by subtle yet dangerous forms of abuse. Because this information is typically not included in traditional domestic violence advocate trainings, advocates may wish to enroll in classes with a special focus on coercive control.

Understanding and Documenting Coercive Control: Executive Summary Workshop is a 90-minute online course designed to help survivors, service providers, advocates, and allies recognize and document coercive control. In this self-paced workshop, you will gain a deeper understanding of coercive control and covert abuse while learning how to identify and document different forms of abuse safely and effectively. The course will walk you through the process of building a concise, impactful two-page summary tailored to each survivor’s unique situation, audience, and goals.

Click here to learn more and sign up!

Education is key to protection from and prevention of subtle forms of abuse. Learning about covert abuse and coercive control helps empower survivors and advocates with the knowledge to recognize, address and overcome abuse effectively. Make sure to check out these articles and videos to learn more.

Many states offer 40-hour domestic violence certification programs. Obtaining a 40-hour domestic violence training certification, in addition to specialized classes focused coercive control, is ideal to become a well-rounded advocate prepared to assist survivors dealing with different forms of abuse.

Here are a few 40-hour advocate training resources based in California:

Survivor resources:

For survivors escaping an abusive relationship, it can be overwhelming to navigate available resources. We created a directory of resources on our website to help make this process easier for both survivors and advocates.

Click here for our directory of resources!

In our directory of resources, you can browse organizations and services sorted by the following locations:

Thank you for joining us in our mission to empower survivors, train providers and educate the community to break the cycle of covert abuse and coercive control in intimate partner relationships.

Together, we can advance our vision of a world in which every adult and child can exercise their fundamental human right to live in peace, safety and freedom in their own home.

About the educator, Ruth Darlene:

Ruth Darlene is the founder and Executive Director of WomenSV (Women of Silicon Valley). Ruth developed the program to address the risks and challenges of more subtle but still dangerous forms of abuse in intimate partner relationships. Founded in 2011, the Los Altos-based nonprofit has since worked directly with over 1500 survivors and hundreds of community partners to raise awareness around coercive control and covert abuse.

In addition to supporting survivors by maintaining a directory of resources, she does public presentations and offers trainings to assist providers in becoming more trauma-informed in working with survivors of covert abuse and coercive control, particularly those involved with a powerful, sophisticated intimate partner.